Home, or at least the idea of home, are not just points on maps. For some, they represent investments for the future while for others, universal sanctuaries and places of communion and safety. As a country synonymous with change and progress, Singapore’s landscape has been terraformed. From kampungs and cemeteries, dense jungles and tropical maladies, the country has transformed from one of the worst housing crises in the world to a place where 90% of its citizens own their own home. And although our physical homes have changed irrevocably through the decades, our own emotions and attitudes have adapted to these upheavals as well.

Photographer Koh Kim Chay, 61, has been documenting changes in Singapore since the mid-80s. An avid street-walker and lover of old Singapore, he remembers that “[i]n Pickering and George Street, the rows of Chinese coffin shops fascinated me, and in the street market of Chinatown, I watched exotic animals being slaughtered for sale. All of these are gone. The rapid economic progress that started in the 1970s saw the demise of much of our architectural heritage”. Working with Kim Chay is photographer Eugene Ong, 39, who has edited copious amounts of negatives and researched on these vanished scenes.

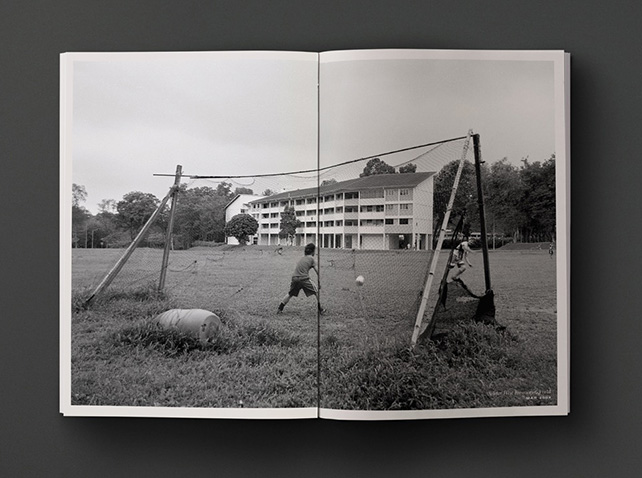

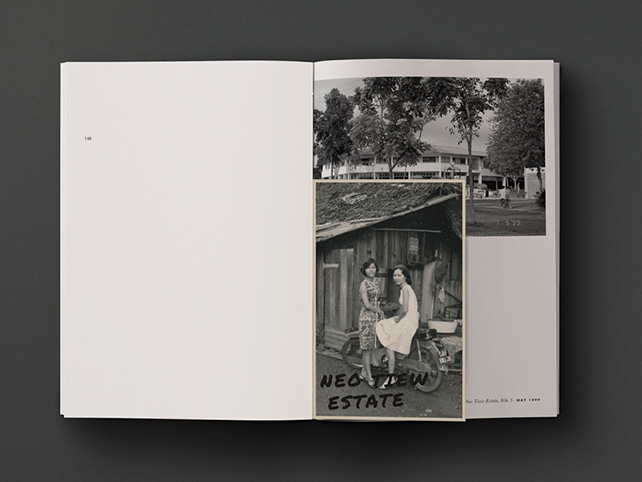

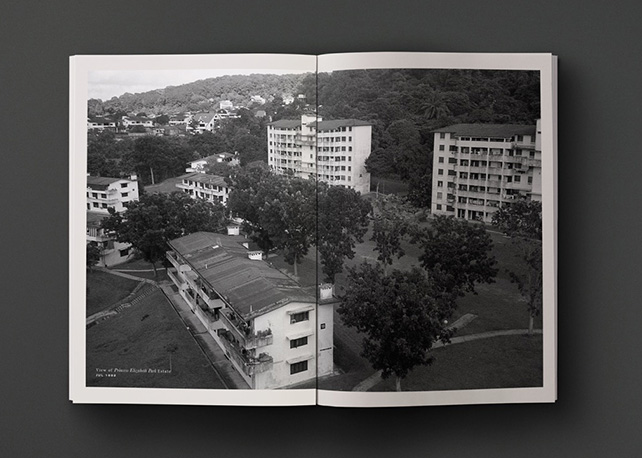

Part of this two-decade long effort to remember Singapore’s past has been formalized into a photographic body of work — Singapore’s Vanished Public Housing Estates. Shot on analog film and mostly developed in the traditional darkroom, the publication features photographs of 27 early public housing estates and precincts with an introduction to the photographer’s work and vision.

From the lush expanse of colonial-era Princess Elizabeth Park estate to the brick-clad heights of Pickering Street, these photographs are not turn-of-the-century archaic but neither are they contemporary enough to be familiarly recognized — especially to a younger generation of Singaporeans. Some of the photographs feature Singapore’s dwellings constructed by the SIT (Singapore Improvement Trust) in their last standing days. Others showcase the newer generation flats in ‘refurbished’ or newly emerging estates then, with their concomitant architectural features and recognizable amenities, though all these have been expunged already.

Accompanying these photographs are postcards, vintage maps, HDB (Housing Development Board) eviction notices and other memorabilia related to the estates. Each works associatively and non-verbally to activate the past as something that was lived in; pockets of domestic drama that although enacted years ago are not difficult to reimagine. As pictorial records of our first homes in historically significant and newly emerging estates then, they are an invaluable window into Singapore’s changing housing landscape in the 50s and beyond.

Singapore’s Vanished Public Housing Estates is designed by Do Not Design, a creative agency specializing in work for art, culture and commerce.

The project currently needs supporters on its crowd funding campaign, which is available at this link https://igg.me/at/svphe